Billions at Work: Latvia’s EU Funding Puzzle

Twenty years inside the European Union have altered Latvia’s economic landscape in visible ways: roads and bridges, labs and industrial parks, digitised public services and cleaner energy systems. Since accession in 2004, roughly €18 billion of EU funding has been invested in Latvia across thousands of projects - a scale that would have been impossible to finance domestically.

What matters now is not whether “Brussels money” arrives - it does - but which type of EU money we win, and how quickly we can turn it into productivity and growth. On that test, Latvia has a split report card: strong on the big, nationally co-financed programmes; weak where innovation and intellectual property are forged.

“EU money” is not one pot but three channels. EU financing arrives through three distinct channels, each with its own rules and speed.

Indirect management is the finance lane. The Commission delegates to partners such as the EIB/EIF under InvestEU, with capital reaching firms via ALTUM or LIAA and commercial banks as loans, guarantees or equity - often the fastest way to close the co-financing gap for grant projects or scale investments.

Shared management funds - ERDF, ESF+, the Cohesion Fund, the Just Transition Fund and the CAP - are negotiated with Latvia and then implemented through national calls by CFLA and line ministries. You co-finance, procure and deliver; the state reimburses eligible costs and settles with Brussels. This is the backbone for productivity upgrades, energy efficiency, skills and infrastructure.

Direct management programmes - Horizon Europe, the EIC and Erasmus+ - are designed and awarded in Brussels. You pitch on the Funding & Tenders portal, often in international consortia; if you win, funding arrives straight from the EU against milestones. This is where deep-tech, IP and cross-border partnerships get built.

Across the 2021–2027 period alone, Latvia’s public-investment envelope is large. Cohesion-policy allocations (ERDF/CF/ESF+) are ~€4.6 billion (similar to 2014–2020). The CAP Strategic Plan 2023–2027 totals ~€2.5 billion. The Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) allocation is ~€1.97 billion, with the third payment of €293 million disbursed on 14 May 2025.

Taken together, ~€10.5–€11.5 billion of EU flows are realistically in play this period when you include shared-management funds, the RRF and direct-EU programmes - before any crowding-in from InvestEU and national co-financing.

Yet these commitments are not automatic. Under both the RRF and CEF, disbursements are tied to milestones; missing targets can delay payments or even trigger reductions.

In the Rail Baltica example, the headline is mixed. In Nov 2024 Latvia secured €397.7 million in CEF Transport grants for RB works, and in July 2025 the EU approved €295.5 million more under the 2024 CEF calls. That pushes cumulative RB-related EU support for Latvia above €1 billion, even as the updated first-phase price tag for Latvia exceeds €6.4 billion, underscoring a demanding execution agenda while Brussels keeps co-financing.

The fact that Latvia was able to negotiate and secure additional support shows it can deliver when large infrastructure is at stake. But this is only one strand of the wider funding picture. Latvia has consistently prioritised infrastructure, while other portfolios - human capital, research and innovation, business competitiveness - seems harder to mobilise and depend on converting approvals into contracts, procurements and timely claims.

With billions still to deploy, the challenge is no longer about access to EU funds but about absorption across all programmes - a task that requires steady tracking, consistent execution, and a focus on results well beyond bricks and rails.

Are we actually at risk of losing 2021–2027 money?

Quick rewind. In early 2024 the mood was grim. A Finance Ministry status note flagged “very high risks” to getting the new 2021–2027 money moving - Cabinet Regulations lagged, open calls were limited, and few projects were under implementation. Media raised attention into a possible ~€500 million 2024 gap if momentum failed to improve.

What changed?

In March 2024 the government reallocated €662.8 million inside the programme to prioritise execution-ready projects - without cutting any ministry’s envelope - and pushed approvals to unblock the pipeline.

The latest Finance Ministry/CFLA update shows clear acceleration and a full-absorption outlook: investment rules approved €3.6 billion (~85%), calls opened €3.2 billion (~76%), and €2.1 billion (~50%) already under contract. The RRF stands at €1.8 billion (92%) contracted, €835 million (42%) paid, with 59% of milestones achieved. The state has also implemented 95% of its EU-fund simplification plan, aiming to cut bureaucracy by ≥25% by 2026.

Where the bottlenecks were - and what to watch.

Latvia’s procurement machinery and permitting times took time to recalibrate to the new rules, but the policy response is visible: the simplification plan is largely implemented, process improvements in project selection are rolling, and a structural reform of the public-procurement system was submitted to Cabinet in August 2025. These steps should keep the pipeline flowing into 2026–2027 as larger transport, energy and human-capital investments move to contracting and works.

The only formal risk that remains.

The EU’s de-commitment rule is N+3 for 2021–2026 commitments and N+2 for 2027 commitments, meaning the final-year envelopes must be absorbed and claimed by 31 Dec 2029. For Latvia, that puts a premium on front-loading large procurements and ensuring payment claims don’t bunch at the finish line.

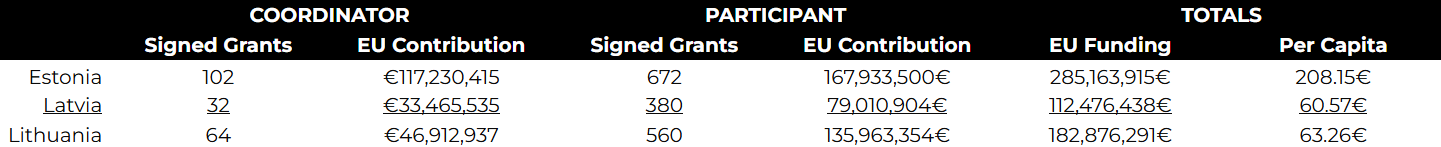

The numbers from the Horizon Europe dashboard paint a stark picture. Of the ~€44 billion in signed grants awarded so far under the programme, Latvia has secured ~€112 million - far behind Lithuania’s ~€183 million and Estonia’s ~€286 million. On a per-capita basis, this translates to ~€60.6 per resident in Latvia, compared with the EU average of ~€118 and Estonia’s ~€209. (All figures as shown on the Horizon Europe Dashboard at the time of writing.)

The disparity is even clearer in project leadership. Estonia leads with 102 coordinator projects, Lithuania follows with 64, while Latvia has only 32. These coordinator roles are critical; they shape project strategy and command a larger share of funding. Latvia’s 380 participation roles, by contrast, are often limited to narrower work packages, bringing less financial and strategic value. (Source: Horizon Europe Dashboard)

As we know, in order to succeed you must try - sometimes again and again. The Horizon Dashboard also shows participation rates in the current programme. As of 8 August this year, Latvia posts the lowest participation numbers across the Baltics and almost half Estonia’s on several metrics. (Source: Horizon Europe Dashboard)

In comparison to a relatively smaller country, this highlights a serious problem: many Latvian projects either do not know they can get funding from Europe or do not apply.

Statistics also cover private-sector participation. Shares are similar across the Baltics - ~25–28% of participants - but in Latvia, much of this involvement is concentrated in state-owned enterprises, leaving independent SMEs under-represented. Notable exceptions include NACO Technologies (EIC Accelerator €2.3 million) and SIA Semantic Intelligence (€75,000 for an AI project). Yet such success stories are rare, and most Latvian SMEs remain disengaged from EU innovation programmes. (Source: Horizon Europe Dashboard)

A major barrier is the co-financing requirement, which can demand ~30% or more of project costs from participants; many businesses and educational institutions lack either the capital or the support structures to meet these obligations, discouraging applications and limiting growth.

The role of professional support

Another major problem is not seeking professional help. From Horizon EU data, approximately a quarter of proposals are deemed ineligible or non-compliant at submission because of application errors; and among correctly submitted proposals in the Baltics, roughly one in five succeeds - numbers that are broadly in line with EU averages. Our conclusion from practice remains: too few Latvian projects use experienced bid support.

Latvia’s weak performance in Horizon Europe and other direct EU programmes stems from limited innovation capacity, as the European Innovation Scoreboard (EIS) 2025 shows. Competitive EU grants flow to countries with strong R&D ecosystems, private-sector investment, skilled talent, and access to financing - and these are precisely the areas where Latvia still lags. The data reveal both the reasons for underperformance and the cost of missing out.

Latvia is ranked an Emerging Innovator, with a Summary Innovation Index (SII) of 56.7 (EU = 100), 25th among 27 Member States. Since 2018, the country’s score has grown by only +4.9 points, compared to the EU average of +12.6. In sharp contrast, Estonia recorded the fastest innovation growth in the EU, surging by +30 points to reach an SII of 104.8 and earning Strong Innovator status. Lithuania advanced by +17.4 points to 81.0, consolidating its position as a Moderate Innovator.

Breaking down Latvia’s scores shows the bottlenecks clearly. Finance and support sits at just 35.5, with venture capital availability collapsing to 24.2 (a 235% drop since 2018), while direct and indirect government support for business R&D is only 4.4, the lowest in the EU. This matters because most EU programmes, including Horizon, require substantial co-financing - a hurdle that affects not only private companies but also universities and research institutes struggling to secure the matching funds needed for proposals.

Digital infrastructure is solid, scoring 87.5 for high-speed internet access, and Latvia’s human capital base is strong, with post-secondary education levels at 105.1 (above the EU average) and a significant share of graduates in STEM fields. This shows that Latvia does not lack ideas, talent, or ambition. What’s missing is the financial and institutional framework to turn that potential into competitive, scalable innovation projects.

The cost of underperformance is high. Latvia misses out on grants that finance advanced labs, prototypes, patents, and deep-tech ventures - investments that drive productivity and create high-skilled, high-wage jobs. While Latvia performs well in areas like trademark applications and CO₂ productivity, these strengths do not compensate for the absence of a deeper R&D base and internationally connected innovation ecosystem. Without significant improvements in business R&D investment, venture financing, and co-financing capacity, Latvia will continue to underperform in direct EU programmes, while neighbours like Estonia and Lithuania convert their stronger ecosystems into faster growth and a larger share of EU funds.

Closing Latvia’s innovation gap with the rest of Europe requires more than acknowledging the problem - it demands sustained investment, smarter execution, and consistent participation in competitive EU programmes.

If Latvia combines higher investment with better co-financing and smarter bidding, it can capture more funding, more partnerships, and more of the know-how that fuels growth in Europe’s most innovative economies.

And there is hope. In today’s world, where efficiency is rapidly accelerating through automated AI solutions that learn as we go forward, these problems can be addressed faster than before. Embracing new technologies is crucial, as they are a complete game changer. Not using them will leave us further behind. Venture Faculty AI procurement and grant solutions are already driving greater results, and from our own experience, their smart use can make a decisive difference. The key is balance: using AI intelligently to scale results without losing human oversight.

Latvia is not lagging in EU funding overall; we excel at the large, co-funded programmes and continue to secure Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) money for flagship infrastructure projects. Where we are falling behind - and where it will hurt most now and in the long term - is in competitive, direct innovation funding.

Closing that gap means raising public and private R&D investment, making co-financing painless, and professionalising the way bids are prepared - starting as partners in consortia, then moving to co-lead, and ultimately to lead roles.

Participation in Horizon Europe and related programmes is not only a way to secure funding but also an entry point into cutting-edge research and innovation networks. Every proposal, even if unsuccessful, builds expertise and credibility, while successful projects provide direct access to advanced technology development, international collaboration, and deep know-how that cannot be replicated with domestic programmes alone.

As we live in an ongoing revolution of AI that is advancing with bigger and bigger steps, reshaping labour productivity and innovation, there is no other way forward than to use AI to close this gap. Those who harness AI will accelerate ahead, and those who do not will fall further behind. Latvia faces a clear choice: move quickly or risk sliding into underdevelopment through lack of ambition.

Our neighbours prove it can be done. Estonia and Lithuania have shown that with deliberate strategy and sustained investment, small countries can play above their weight in Brussels-run programmes. Brussels is not the ceiling - our execution is.

Authors: Manager, Edgars Poga and Analyst, Tomass Vilks at Venture Faculty